Long before artificial intelligence, photographers altered images to burnish the reputations of politicians—from Lincoln to Stalin.

The rise of artificial intelligence or AI has made photo manipulation easier and more accessible than ever. And under the right circumstances, these images could wreak political havoc.

Generative AI-powered tools can create new images or videos, including so-called deepfakes. “Originally, deepfakes referred to videos in which the face of one person had been swapped with the face of another using AI,” says Matthew Stamm, an engineer at Drexel University in Philadelphia. “As generative AI has progressed, the word deepfake has been also used to describe many other forms of fake or manipulated [images] made using AI.”

When deepfakes feature political leaders, they risk spreading misinformation or discrediting administrations. (Here’s how to identify a manipulated photo, according to experts.)

The AI tools that produce fake images may be novel, but there’s nothing new about the act of editing photographs for political spin. Long before deepfake entered the lexicon, manipulated photographs in the 19th and 20th centuries attempted to shape the image of world leaders.

Early photo editing techniques

As long as there have been photographs, people have been editing them. Photography pioneers believed pictures were more than objective records of reality. Photographer Henry Peach Robinson wrote in 1869, “I am far from saying that a photograph must be an actual, literal, and absolute fact; […] but it must represent truth.”

The head of the above photo of Grant at City Point likely comes from this June 1864 portrait of Grant standing next to a tree in Cold Harbor, Virginia.

What kind of truth, though? Photographs could enliven a lifeless corpse to comfort a bereaved family or showcase the patriotism of a soldier heading to war.

Shaping these truths sometimes meant altering the photograph. “In the darkroom, [photographers] had lots of control over framing and the relative exposure of an image,” explains Tanya Sheehan, an art historian at Colby College in Maine. “Negatives could be double-exposed. Multiple photographic negatives could even be cut and recombined to produce composite images.”

Making leaders look good

Studios also touched up photographs to enhance sitters’ appearance. “People who frequented photographic studios expected their portraits to show their ‘best selves,’ and retouching was seen as crucial to that goal,” Sheehan points out.

Political leaders and their supporters were no exception.

In this portrait of President Abraham Lincoln, Lincoln’s head was superimposed onto the body of John C. Calhoun in an earlier portrait.

COMPOSITE PRINT BY WILLIAM PATE (LEFT) AND PRINT BY ALEXANDER HAY RITCHIE (RIGHT)

Around 1865, a new image showed Abraham Lincoln in a regal pose. It’s possible the depiction was created after the wartime president’s assassination had transformed him into a “martyr,” and it may have circulated after his death. The photo later turned out to be a fake: Lincoln’s face had been cropped onto the body of John C. Calhoun, a pro-slavery politician.

Decades later, the Soviet Union deployed similar techniques to make strongmen look even stronger, especially during the regime of Josef Stalin from 1924 and 1953.

“At the state level, most photo doctoring was carried out by the art departments of various official publications, journals, and newspapers, which used a range of different means to manipulate images,” says Jessica Werneke, a historian at the University of Iowa.

“Airbrushing […] was common to remove physical imperfections, specifically in images of Stalin, who had scars from smallpox and injuries to the left side of his body from a childhood injury.”

Excising political liabilities

Photo manipulation also served a more nefarious purpose during Stalin’s regime. “[It] was a means of rewriting history according to Stalinist policies and principles,” says Werneke. “Stalin and his supporters took this process to a whole new level in physically erasing individuals from images.”

Nikolai Yezhov (right) lead the Soviet secret police from 1936 to 1938 under Joseph Stalin (center). Yezhov was was arrested in 1938 and executed in 1940. After his execution, Yezhov was painstakingly removed from this image, earning him the posthumous nickname “the Vanishing Commissar”.

PHOTOGRAPH VIA UNIVERSAL IMAGES GROUP/GETTY IMAGES

Arguably the most infamous case of political erasure involves a pair of photographs depicting a scene from 1937. The first image, printed that year, features Stalin and three colleagues, including secret police official Nikolai Yezhov. Three years later, the image appeared in print again––without Yezhov.

What happened? After the image had first been captured, Yezhov fell out of favor. By 1941, he had been executed and was literally and figuratively cut out of the picture, as if he had never been near Stalin to begin with.

Identifying fakes

Mikhail Gorbachev, then Russian Politburo member and second in line at the Kremlin, in Edinburgh, Scotland, 1984.

PHOTOGRAPH OF BRYN COLTON, GETTY IMAGES

An official portrait of Gorbachev with his famous birthmark edited out.

PHOTOGRAPH FROM THE COLLECTION OF THE WENDE MUSEUM

Today, organizations like the Content Authenticity Initiative can help vet digital images and detect AI’s influence. But what about pre-digital photographs have been heavily manipulated?

According to Micah Messenheimer, the Library of Congress’s curator of photography, provenance is key: “Knowing the photograph’s history […] helps establish its authenticity.”

Provenance is only part of the puzzle, however. “Expert conservators can examine the physical properties of a photograph to understand when something is out of the ordinary in the chemical composition, paper age, or applied coloring,” explains Messenheimer.

Sometimes, all it takes is a feeling that the photo doesn’t look right. Helena Zinkham, chief of the library’s Prints and Photographs Division, recalls how Kathryn Blackwell, then a reading room assistant, first raised suspicions in 2007 about a photograph featuring Ulysses S. Grant in what appears to be a military camp during the Civil War.

This image of Major General McCook photographed between 1862-1865 was likely used as the horse and man’s body in the composite photograph of Grant at City Point.

Blackwell “was refiling the photo one day and thought, ‘Something’s off here.’” Detective work revealed the image was a composite of different sources. Grant’s head had been cropped onto another officer’s body, and the whole scene was cast against a background from an entirely different photograph. Researchers dated the image to sometime around 1902, well after Grant’s death in 1885.

The image portrayed Grant as a war hero, nobly posing on a horse.

The means of manipulating photographs have changed over time, but the goal remains the same: to shape the image of political leaders, one edit at a time.

News

America is still dealing with the pandemic’s scars, psychologists say

Many people have found themselves lonely and exhausted but anxious about connecting with others. Here’s why experts are worried about the loss of unplanned, informal interactions. In the years since lockdown, many people—especially youth—have found themselves in a catch-22: lonely…

These ancient cities sunk to the ocean floor. Here’s how they were rediscovered.

Lost cities sunken beneath the waves are not just myths. Many coastal communities were swallowed up by the sea in the ancient world—their streets, homes, and temples all submerged under relentless tides. For millennia legends swirled about these places, but…

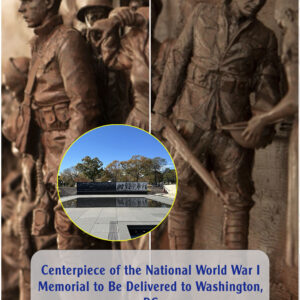

Centerpiece of the National World War I Memorial to Be Delivered to Washington, DC

Photo Credit: DANIEL SLIM / AFP / Getty Images Almost a decade in the making, the centerpiece of the National World War I Memorial is finally slated to arrive in Washington, DC. The 58-foot-long, 10-foot-tall bronze sculpture, called “A Soldier’s…

Offset Finally Speaks Out On Why He Chose Jade Over Cardi B Despite Having Two Children With Cardi B

Offset Opens Up About Choosing Jade Over Cardi B: A Closer Look Into Celebrity Relationships. In the whirlwind world of celebrity relationships, where headlines are often dominated by twists and turns, one particular love triangle has captured the attention of…

Cardi B Gets Into A Dispute With Milagro Gramz Following A Mishap At The Bet Experience Show.

Cardi B headlined the BET Experience Concert Series in Los Angeles, marking its return this weekend, but encountered technical difficulties during the show. Known for her passionate performances, Cardi B expressed frustration towards the production crew for missing cues, prompting…

Offset Finally Speaks Out On Why He Chose Jade Over Cardi B Despite Having Two Children With Cardi B

Offset Opens Up About Choosing Jade Over Cardi B: A Closer Look Into Celebrity Relationships. In the whirlwind world of celebrity relationships, where headlines are often dominated by twists and turns, one particular love triangle has captured the attention of…

End of content

No more pages to load