The South African baboon that became a war hero

Article Author/s:

Vincent Carruthers

Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Ninety-nine years ago, on 22 May 1921, a young corporal in the 3rd South African Infantry Regiment died. What distinguished him was that he was a Chacma baboon. The story of Jackie the baboon has often been told and forgive me if you have heard it before. The reason for making it a Magalies Memoir is that Jackie was born in the Magaliesberg. Some details have become confused during a century of re-telling, but essentially the story is as follows:

Private Albert Marr and Private Jackie the Baboon at the end of the war.jpg

Private Albert Marr and Private Jackie at the end of the war

Jackie was found as an infant by Albert Marr (some accounts refer to him as Andrew) on the family smallholding in Villieria, now a suburb of Pretoria on the southern side of the Magaliesberg. He had probably been orphaned by bounty hunters who were paid by the Transvaal government to shoot baboons raiding crops in the Moot Valley. Albert took the young baboon home and he was raised as a member of the family much like a human child. Jackie and Albert became inseparable.

In 1914 South Africa joined the Allies in the First World War and the two-year-old Union Defence Force called for volunteers to serve, first in German South West Africa and then in East Africa. In 1915 the 3rd South African Infantry Regiment was formed to join the South African Overseas Expeditionary Force in North Africa and Europe. Albert Marr volunteered to join the regiment but requested not to be separated from his beloved baboon. Lt. Colonel Edward Francis Thackeray, Officer Commanding the 3rd South African Infantry, agreed to allow Jackie to join as the regimental mascot. (Thackeray’s first cousin, the astronomer Dr A.D. Thackeray, later helped with the establishment of the Leiden University Observatory on the banks of Hartbeespoort Dam – another thread connecting this story with the Magaliesberg). Click here to view the article on the observatories of the Magaliesberg.

Twin telescopes of the Rockerfeller astrograph at the Leiden Observatory Broederstroom – Patrick Moore The Astronomy of Southern Africa.png

Twin telescopes of the Rockerfeller astrograph at the Leiden Observatory Broederstroom (The Astronomy of Southern Africa)

Today most people would be appalled at the thought of taking an animal to war but until quite recently, many regiments had animal mascots. Dogs, goats, horses, a springbok and a kangaroo led their troops in ceremonial parades in the 1914-18 War, and many accompanied their regiments onto the battlefield. Jackie was one of those and, because of his attachment to Private Albert Marr and because of a baboon’s remarkable ability to imitate and learn, Jackie led the life of a full-time soldier. At training camp in Potchefstroom he drilled with the men, carried a wooden rifle, learned to salute an officer and he was reputed to take meals using proper army plates and cutlery. After training he was officially enlisted as a private and issued with a military identity number, pay book, ration card and a specially fitted uniform and cap, complete with regimental brass insignia.

The 3rd SA Infantry saw its first action in Egypt against the Senussi, allies of the Ottoman Empire, who were threatening the Suez Canal. The South Africans attacked Senussi at the battle of Agagia on 26 February 1916 and captured the commander of their forces, Jafar Pasha, who later changed sides and eventually became Prime Minister of Iraq. Albert Marr was wounded in the battle and Jackie, frantic with anxiety, stayed with him, licking his wound until the medics arrived.

After his recovery Albert and Jackie re-joined the 3rd SA Infantry and fought in the trenches on the western front. For two and a half more years the baboon stayed with the regiment and shared the horrific conditions of war in France and Flanders. Although not a combatant in the full sense, he stood guard duty with Albert and his acute hearing and eyesight saved lives on more than one occasion.

Some accounts say that Jackie took part in the famous Battle of Delvile Wood in July 1916, but this seems unlikely. The 3rd SA Infantry was there along with the 1st, 2nd and 4th SA Infantry and took command of all the South African units after the other commanding officers had been wounded. The South Africans held the strategically important wood for six days of relentless bombardment, but it was at terrible cost. Of the 3 000 South Africans at the start of the battle, only 140 were unscathed by the time they were relieved. No records indicate that one of them was a baboon.

The shattered remnants of the 3rd South African Infantry continued to fight at the Battles of Arras in April 1917, the Ypres offensive in September and the retreat from Passchendaele in November 1917. Jackie was certainly in most of those actions.

In April 1918, the Germans commenced the Spring Offensive, a massive manoeuvre across the whole western front intended to drive the Allies back before the long-awaited US army joined the war. The 3rd South African Infantry was once more at the front and it was in one of the battles during the Spring Offensive that Jackie was seriously wounded. Accounts differ about precisely which battle, but the description of events is the same in all of them.

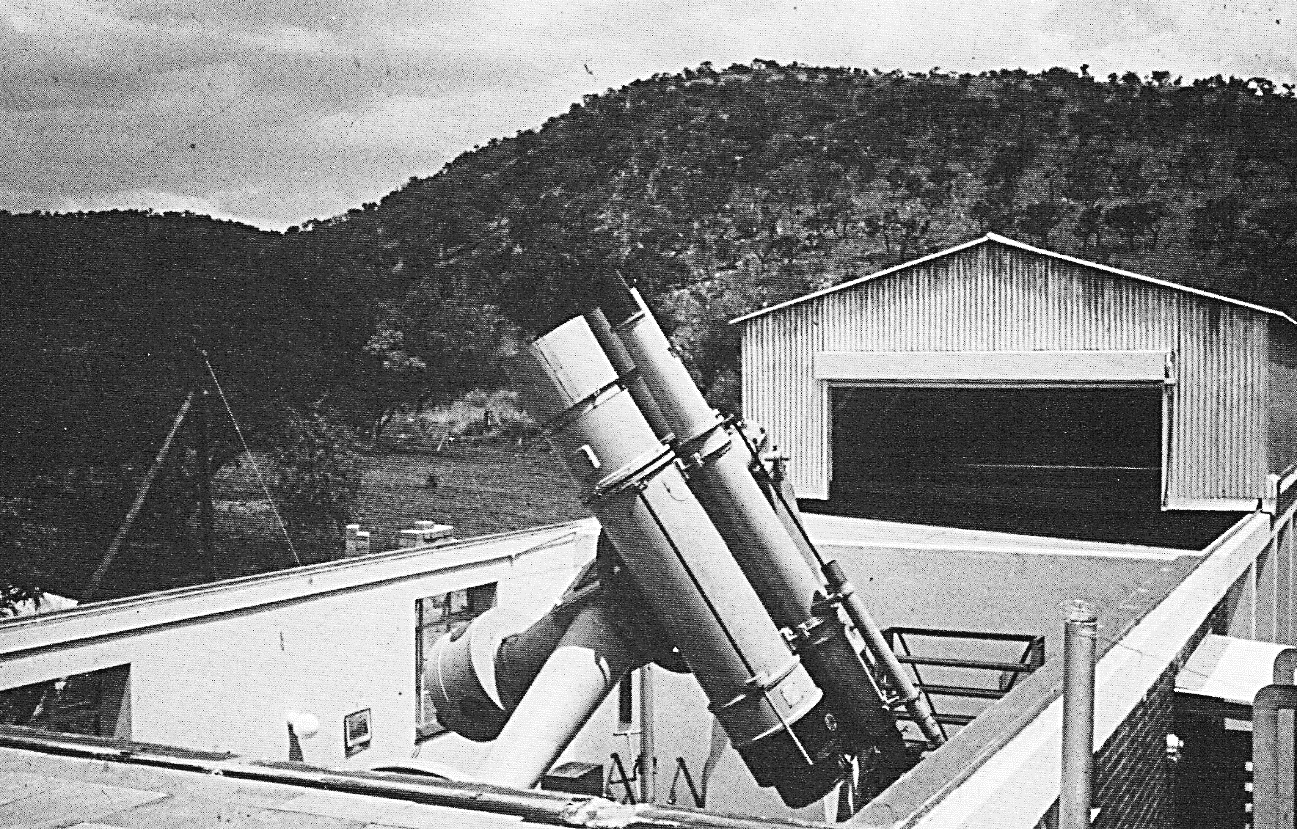

Lt. Colonel Edward Francis Thackeray – SA Military History Society.png

Lt. Colonel Edward Francis Thackeray. Officer Commanding Jackie’s regiment (SA Military History Society)

The South Africans were pinned down under fire and the men hastily built sangars for protection. Jackie was seen to be copying his comrades, piling stones around himself, when he was hit by shrapnel. One paw was injured, and his right leg was almost severed. In agony and fear, he fought off the stretcher bearers who came to his assistance but eventually allowed Albert to carry him off. He was treated by Captain RN Woodsend of the Royal Army Medical Corps who was apprehensive about administering chloroform to an animal. But Jackie survived the anaesthetic and the amputation of his leg and recovered rapidly. He was formally on army strength so, in Captain Woodsend’s words, ‘duly labelled, with number, name. ATS injection, nature of injuries, etc., he was taken by a passing ambulance to the Casualty Clearing Station’.

A few months later with the end of the war imminent, Jackie and Albert were shipped back to England where Jackie was feted as a war hero and a number of decorations were added to his uniform. The right sleeve of his battle dress now bore four Overseas Service Chevrons, one for each year he had served, and on the left sleeve he wore a Good Conduct chevron and a brass ‘Wounded in Combat’ stripe. He was also promoted to Corporal. From September 1918 until February 1919 he and Albert were seconded to the Red Cross to raise funds at various functions. For a small donation, members of the public could shake Jackie’s hand and for a bit more they could kiss him. A photograph of these foolish antics show that Jackie was restrained on a chain, but kissing a recently wounded baboon does not seem very sensible!

The now famous Jackie returned to South Africa and after their official discharge from Maitland Camp in Cape Town he and Albert returned to a welcome parade in Pretoria. The following year Jackie led the 1st South African Brigade in the Peace Parade through the streets of Pretoria where he received the Pretoria Citizen’s Service Medal.

Soon after he returned to the Marr farm in Villieria, Jackie was killed when a fire destroyed the farmhouse. Albert Marr lived until 1973 aged 84.

The ethology of Jackie’s story is as intriguing as his military career. Baboons make notoriously bad pets. If captured as infants, they cling to their human foster parents, quite literally, every moment of the night and day. This is well described in Fransje Van Riel’s book about Karin Saks’s baboon research, My life with Darwin and in Eugene Marais in Soul of the Ape. Clearly, that was the relationship between Albert and Jackie. From the age of two or three years, however, male baboons in captivity often become aggressive, especially when under stress. At that age they develop formidable canine teeth and the situation nearly always ends tragically – usually for the baboon. But, other than when he was seriously wounded, aggressive behaviour is not mentioned in any of the accounts of Jackie during his army career although several photographs show him with a restraining collar and chain. Perhaps the constant presence of Albert kept him happy, or perhaps such incidents have been airbrushed from the narrative. Either way, this story should not be taken as encouragement to own a pet baboon. Let it remain merely a feel-good anecdote about an extraordinary animal.

Main image: A young admirer shakes Jackie’s hand at a fund-raising function.

About the author: Vincent Carruthers has written several books including The Magaliesberg (four editions), Cradle of Life (2019) and The Wildlife of Southern Africa (three editions). In 2006 he initiated the project to have the Magaliesberg region declared a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. He has received awards from various institutions including the University of the Witwatersrand Gold Medal in 2016 and the North West University Chancellor’s Medal in 2013. He has been CEO of WESSA, chairman of Birdlife South Africa and member of the North West Parks and Tourism Board. Currently retired from his management consultancy, he is enjoying writing for the Magaliesberg Association for Culture and Heritage.

News

How Hezbollah & Israel counter-attack after the Lebanon Explosion

How Hezbollah & Israel counter-attack after the Lebanon Explosion This is how Hezbollah responded to Israel after the sophisticated pager and walkie-talkie explosions, which occurred across Lebanon. They retaliated by launching guided missiles for the first time. The three strikes…

[MUST WATCH] In pictures: The deadliest day in Lebanon in nearly a year of conflict

In pictures: Israel strikes hundreds of Hezbollah targets in Lebanon Israel attacked hundreds of Hezbollah targets on Monday in airstrikes, making it the deadliest day in Lebanon in nearly a year of conflict. Smoke billows over southern Lebanon following Israeli…

BREAKING NEWS: US sends more troops to Middle East as violence rises between Israel and Hezbollah

US sends more troops to Middle East as violence rises between Israel and Hezbollah Violence between Israel and Hezbollah is raising risk of a greater regional war. WASHINGTON — The U.S. is sending a small number of additional troops to the…

Easy Company Facts Even Hardcore Fans of ‘Band of Brothers’ Don’t Know

Photo Credit: HBO / Getty Images HBO’s 2001 miniseries, Band of Brothers, has continued to gain popularity in the decades since its release. This is partly due to later generations having greater access to the series – in particular, via…

Mighty MO – USS Missouri (BB-63) Video and Photos

There are three other ships in the United States Navy which were named after the state of Missouri besides the battleship USS Missouri (BB 63), and although she became associated with the history of the Japanese raid at Pearl Harbor, she…

A Soviet TU-16 medium jet bomber flies past the anti-submarine warfare support aircraft carrier USS Essex

That Time A Soviet Tu-16 Badger Crashed Into The Sea After Buzzing A U.S. Aircraft Carrier A screenshot from the video filmed aboard USS Essex shows the Tu-16 Badger flying very low close to the aircraft carrier. Low pass with…

End of content

No more pages to load