In the final stages of the Second World War, both the Allied and Axis powers turned to more extravagant plans in an attempt to bring the deadly fighting to an end. The Americans, for example, planned an invasion of Japan. In response to the proposed Operation Downfall, the Japanese developed many questionable defenses, including kamikaze frogmen and manned torpedoes.

Operation Downfall

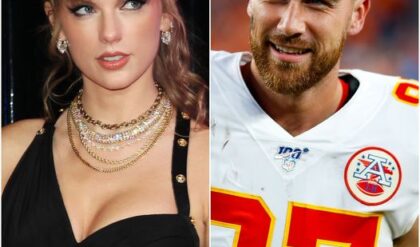

US President Franklin Roosevelt, Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Adm. Chester Nimitz and Adm. William Leahy at a meeting in Hawaii, 1944. (Photo Credit: Unknown Author / US Navy / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

Operation Downfall was the American plan to invade and conquer Japan. It would occur in two phases – operations Olympic and Coronet – and, if it had gone ahead, would have been a larger amphibious invasion than D-Day.

The operation was set to begin in November 1945, once the war in Europe was over. Olympic, the first phase, involved a massive amphibious assault on the Japanese island of Kyūshū, which would be used to launch future troops during Coronet. This second phase would target the Tokyo Bay area with an even larger force around March 1946.

However, the planned invasion was never executed, as Japan surrendered after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, sparing both sides from the catastrophic casualties that such an invasion would have entailed.

Training kamikaze frogmen

Yokosuka Naval Base, Japan, 1942. (Photo Credit: CORBIS Historical / Getty Images)

The Japanese knew an Allied invasion of some sort might occur, so they came up with the idea of Fukuryu attacks to help combat one. Literally translating to “crouching dragon,” these strikes would involve kamikaze frogmen attacking incoming enemy vessels from beneath the water.

This idea was proposed as early as 1944 by Capt. Kiichi Shintani of the Yokosuka Naval Base Anti-Submarine School, Japan. He was worried that, due to manpower and supply shortages, the typical means of defense wouldn’t work and thus he decided to modify the use of swimmers who had been successful in attacking Allied ships earlier in the war, most famously around Peleliu.

These men would live underwater at various strategic locations around the Japanese coast, allowing them to catch the enemy completely by surprise with explosive nighttime attacks. Not only would this prevent them from being seen, but it also meant they’d be less likely to be attacked.

Fukuryu attacks

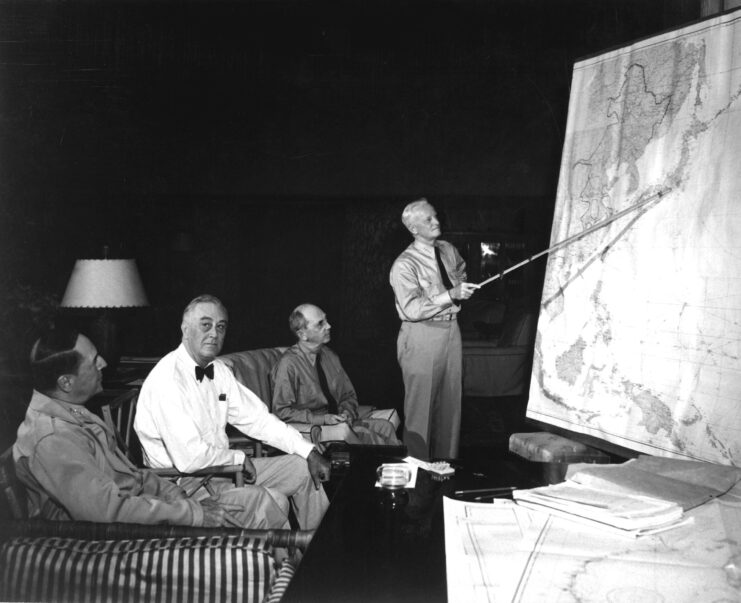

Fukuryu diver in his underwater suit, with a mine on a bamboo spear. (Photo Credit: Meckneck / Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

These kamikaze frogmen would emerge from their hiding places onto the seafloor in diving suits, holding 16-foot-long bamboo spears with Type-5 attack mines attached to the end of them. Each would contain an incredible 33 pounds of explosives and be rigged to explode when pushed up against the hull of a ship passing overhead.

Numerous mines would be placed around the locations of these underwater hideouts, so the frogmen could easily access them. Given the size of the explosives, the men trained for this weren’t expected to survive their mission, if successful. Not only were they on a one-way journey, but they were also signing up for endless lonely hours as they awaited the enemy’s arrival.

Training the kamikaze frogmen

Two Italian frogmen, 1941-42. (Photo Credit: ullstein bild / Getty Images)

Nonetheless, big plans were made to train 6,000 kamikaze frogmen for this role, which required a large amount of specialized equipment. Each would need a diving suit, complete with a jacket, pants, shoes and helmet, as well as oxygen and liquid food to sustain them for around 10 hours underwater. They would also be weighed down at a depth of 16-23 feet by 20 pounds of lead.

Not only did each individual require personal equipment, but there was also a need to create underground hideouts where they could lie in wait for enemy ships. They opted for large concrete stations that would be built aboveground and then sunk to their needed location, although none were ever made. An earlier plan proposed a form of underwater steel foxhole, but this was quickly scrapped when it was realized they made nearby explosives less effective.

Despite extensive plans clearly being made by the Japanese to deploy their kamikaze frogmen, they were never used.

A failed initiative

Fukuryu diver, 1946. (Photo Credit: Unknown Author / US Navy / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

The 71st Arashi were trained at Yokosuka, while the 81st Arashi would undergo training at Kure. Another unit was in the works at Sasebo. However, there were only two battalions fully trained by the time the Japanese surrendered, both with the 71st. The total equaled about 1,200 of the proposed 6,000 frogmen.

Training wasn’t the only thing falling behind, as production also proved difficult. Only 1,000 diving suits were ready at the time of surrender, and none of the real mines were constructed, only dummy ones.

Even though the Fukuryu were never used in combat, many still died during the training. Most of these fatalities were caused by issues with the breathing apparatuses in the diving suits. They were rudimentary, so each diver had to inhale through their nose and out through their mouth into a tank, which would turn the carbon monoxide back into oxygen.

If they mixed the two up, they’d inhale caustic lye and faint while underwater. If any seawater got into the tanks, a mixture was created that, when inhaled, would burn the lungs.

More from us: Flying ‘the Hump’ Required Allied Pilots to Fly Over the Himalayas in Terrible Conditions

Other divers died when they got tangled in plant life on the ocean floor and were unable to free themselves. Ultimately, no enemy combatants were ever killed in Fukuryu attacks, yet so many trainees were that “they couldn’t keep up with cremation.”