During the Second World War, the Allied forces in the China Burma India (CBI) Theater faced a formidable logistical challenge in supplying troops and equipment across vast distances and treacherous terrain. One key solution to this problem was developing a dangerous air route over the Himalayas. Flying “the Hump” required exceptional skill and courage, and, despite the dangers such a task posed, the airlift was critical to the success of the Allied war effort.

China Burma India (CBI) Theater

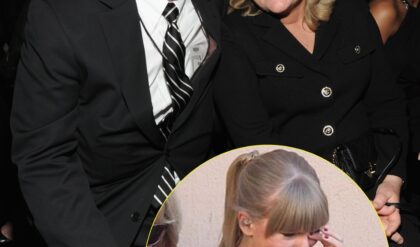

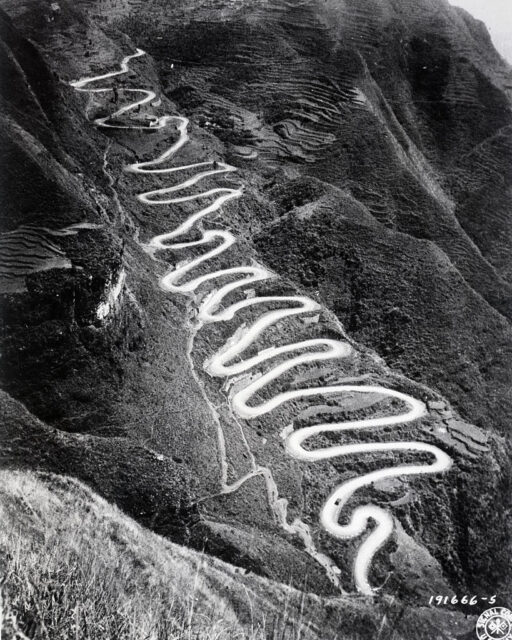

Section of the Burma Road in the China Burma India (CBI) Theater, 1944. (Photo Credit: Bettmann / Getty Images)

Aside from combat in Europe, Africa and the Pacific, Allied troops fought in the China Burma India Theater, with the fighting in China crucial to overall success in Europe. Over a million Japanese troops engaged in combat in China alone, so it was of utmost importance for the Allies to support the war effort there, so the enemy remained where they were. The Allies also saw China as a place from which they could launch air raids on Japan without traveling lengthy distances.

However, it became clear early on that supply routes would be a significant problem. By April 1941, the Japanese controlled all possible routes to supply China, except for the Burma Road. However, the enemy’s success in the region raised questions over how long the Allies would be able to use it.

A dangerous air route

Body of an American ambulance being removed from a cargo aircraft with the India-China Division (ICD), Air Transport Command, 1944. (Photo Credit: Photo12 / Universal Images Group / Getty Images)

Given these concerns, the Allies turned to the air, with the hopes of creating a cargo transport route between India and China. The task of finding such an air route over the Himalayas fell to Chinese Air Force Maj. Gen. Mao Bangchu, which was the only possible option. He was successful, and a flight path was established across the mountain range.

In November 1941, China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC) pilot Xia Pu was the first to fly what became known as “the Hump,” named for the mountaintops, which looked like the humps of a camel.

This was just in time, as, by May 1942, the Japanese had seized enough land that the Allies were completely cut off from the Burma Road. As a result, an agreement was reached between China, the United States and other Allied nations to maintain a continual airlift between Assam, India and Kunming, China. The role of maintaining this airlift was given to the US Army Air Forces (USAAF) Tenth Air Force, then to the India-China Division (ICD) of the Air Transport Command.

Flying ‘the Hump’

Air Transport Command Commander Brig. Gen. William H. Tunner, 1943. (Photo Credit: U.S. Air Force / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

Flying “the Hump” was dangerous, to put it lightly. The route was 500 miles long and required pilots to navigate extremely high altitudes. This increased the likelihood of extreme turbulence and heavy ice accumulation on the airborne craft. As if that wasn’t bad enough, it wasn’t uncommon for “the Hump” to see monsoon-like rains, fog and wind that reached 100 MPH.

How was this dealt with? By issuing a “no weather” proclamation. This meant that no matter the weather, “the Hump” was never closed to flights.

While, obviously, there were Japanese fighter pilots waiting to pick off aircraft flying this route, they were the least of the Allies’ worries. Some sources say the bad weather killed more pilots than the Japanese, with Air Transport Command Commander Brig. Gen. William H. Tunner writing in his memoir, “Flying the Hump was considered as hazardous as flying a combat mission over Germany.”

Terrifying conditions

American aircraft flying “the Hump” toward China, 1944. (Photo Credit: Mondadori / Getty Images)

These dangerous conditions led to extremely high losses among those who flew “the Hump.” Another possible contributing factor was that many of the pilots were newly trained and had only a bit of experience. The many Chinese aviators were familiar with the route, but the Allies were not.

Their desire to go home was also a significant problem, as many of the pilots would try to tally up as many flying hours as possible to earn their leave. Tunner’s flight surgeon reported that half of the men suffered from operational fatigue, which contributed to only more accidents.

Heavy losses were suffered while flying ‘the Hump’

Hump Memorial in Kunming, Yunnan province, China. (Photo Credit: MyLoupe / Universal Images Group / Getty Images)

These many factors caused high fatalities, with roughly one-third of the men dying. Even those with exceptional qualifications struggled. For example, Gen. Henry H. Arnold and the combat crew transporting him got lost because of the lack of oxygen at high altitudes.

Supposedly, at least 468 American and 41 Chinese aircraft were lost while “the Hump” was in operation. With them were 1,314 air crew and passengers. Many others were reported missing, and some of these men eventually reappeared, either walking into their bases or being rescued by others.

January 6, 1945

Capt. Lee Hamilton, prior to his last flight over “the Hump,” 1945. (Photo Credit: Paul Chinn / The San Francisco Chronicle / Getty Images)

Undoubtedly, the most notable and tragic day flying “the Hump” was January 6, 1945, sometimes called the “Night of a Thousand Maydays.” Although William H. Tunner had his men check the weather before leaving, they were too far to see anything that was amiss. Little did they know that two storm fronts had joined together, creating a horrific winter typhoon near the Irrawaddy River gorge in Burma.

That night, over 100 aircraft took to the skies, and it didn’t take long for warnings of severe weather to come back to base. It was some of the worst readings reported in the entire China Burma India Theater. January 6 also turned out to be the most deadly for those men. The radios were clogged with mayday signals and their final words, like one unidentified pilot’s.

Murray Scott, who survived that night, vividly remembered the words of another pilot never heard from again: “I seem to be lost, and there’s six inches of ice on my control surfaces. We can’t hold height, so we’re bailing out now. So long.”

A total of 15 aircraft crashed or went missing, while 18 crewmen and nine passengers were killed.

Overall effectiveness of flying ‘the Hump’

German children cheering an American cargo aircraft as it flies overhead during the Berlin Airlift, 1948. (Photo Credit: Bettmann / Getty Images)

Given the heavy losses on January 6, 1945 and throughout the rest of the airlift, the question shifts to whether or not this route and its purpose were effective. Those flying “the Hump” were, perhaps unbeknownst to them, partaking in the first large-scale airlift.

The Allies delivered 650,000 net tons of supplies throughout World War II, reaching a monthly maximum of 71,042 tons in July 1945. Of this total, CNAC pilots ferried about 12 percent. In addition to these supplies, there were also 33,400 people transported in various directions using “the Hump.”

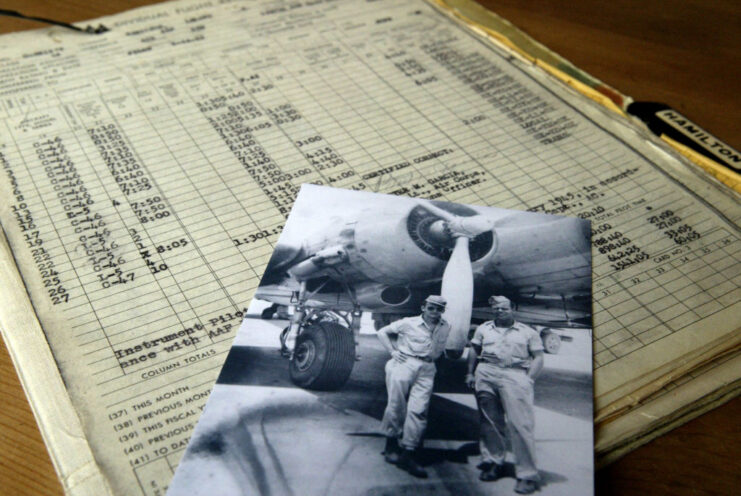

It’s no wonder these numbers are so high, given the magnitude of the airlift. However, as the years went on, the experience of these pilots and crew grew and the number of losses decreased. Allied and Chinese pilots logged 1.5 million flight hours alone, with the Air Transport Command making 156,977 trips east between December 1, 1943 and August 31, 1945.

More from us: Mel Brooks: The Famed Jewish Comedian Who Fought the Germans In Europe

Not only did flying “the Hump” prove that an airlift of this kind was possible, but it was also strategically effective. The West implemented similar efforts during the Berlin Airlift between 1948-49 and the Korean War.