Many people have found themselves lonely and exhausted but anxious about connecting with others. Here’s why experts are worried about the loss of unplanned, informal interactions.

In the years since lockdown, many people—especially youth—have found themselves in a catch-22: lonely and exhausted but anxious about connecting with others.

PHOTOGRAPH BY OREDIA, PATRICE LUCENET/CAMERA PRESS/REDUX

ByAlissa Greenberg

July 25, 2024

When Jessica Hernandez’s best friend from college died of cancer in April 2020, she attended the funeral the only way she could under a COVID-19 shelter-in-place order: via Zoom. Her heartache persisted as COVID-19 death rates dropped and the national state of emergency expired, transitioning us into a new era of living with the virus.

Once Hernandez was finally able to grieve with her friends in person, she started to heal, but the process has been slow. As a licensed social worker and trauma therapist, she has noticed that many of her clients have experienced similarly prolonged distress unique to the last four years.

For many people like Hernandez around the world who experienced explicitly traumatic experiences during lockdown, this lingering grief seems easier to account for. But four years on, a new pattern is emerging: even those who did not lose loved ones, their livelihood, or their health (with chronic conditions like long COVID, for example) are still dealing with a diffuse, vague sense of wrongness.

Experts say this ambiguous distress manifests in omnipresent, heightened loneliness, sapped social capacity, and withering bonds with community—and that calls to push through and “return to normal” make it impossible to do just that.

Turning inward to weather the storm

While it’s impossible to draw explicit cause and effect from the last few years of lockdowns and heightened disease, geopolitical upheaval, and extreme weather and inflation, it’s clear that the American emotional landscape is now in turmoil.

A 2022 survey from the American Psychological Association showed that one third of Americans found stress “completely overwhelming for them most days.” In a later poll poll, almost half of respondents reported they were more anxious in 2024 than they were last year. And one third of Americans report feeling lonely at least once a week, while 10 percent feel lonely every day.

Health geographer Jessica Finlay, who has been following a cohort of 7,000 older Americans across all 50 states since 2020 to track the ways they’ve coped with COVID-19, sees this distress as part of the emotional legacy of lockdown. “People turned inwards toward close friends and community members to weather the storm,” she says, relying on them while closing off to the outside world.

But that protective stance has consequences. “When people are scared, they get simple, they get closed” to the connections we need, says therapist Naomi Altman. Even long after lockdowns have eased, many Americans seem to be struggling with this social catch-22. “I see people conflicted with wanting to be less lonely, wanting to meet people, but feeling very anxious or nervous about getting out and doing it,” says clinical psychologist Robin Fox.

Teens and twenty-somethings appear to be having an especially difficult time. In a recent pilot study separate from her coronavirus cohort, Finlay found the highest levels of loneliness and isolation in respondents ages 15 to 20. But people of all ages complain of a combination of diminished social battery and increased apprehension that Finlay refers to as “social muscle atrophy.”

Hernandez, Altman, and Fox have all also noticed that their clients now often have a hard time relaxing, are hyper alert to danger, and struggle with mood swings and difficulty regulating emotions. Licensed marriage and family therapist Sam Silverman says all these symptoms are typical indicators of both unprocessed trauma, and “nervous system burnout,” where prolonged hypervigilance and distress lead to permanent exhaustion and overwhelm.

This distress appears to correlate to rising addiction: research shows mental health struggles were the most common reason for alcohol and other substance abuse during the pandemic. According to the CDC, annual overdose deaths have steadily increased since 2020, along with calls to the 988 suicide hotline., The CDC’s latest report shows suicide at a high not seen since 1941.

Weak ties and the workplace

One lingering consequence of the lockdown era is that it taught us “to fear other people,” Fox says. In particular, Finlay worries about the loss of what sociologists call “weak ties,” informal, unplanned interactions that decades of data show are associated with higher life satisfaction and even longer life expectancy.

Now, many people in her cohort feel they have neither the skill nor the opportunity for those interactions. Instead of chatting with the cashier or the person at the butcher counter, “whether by habit or on purpose or both, people rush through grocery store. They get what they need and get out,” she says.

Weak ties are more likely to bridge across age, race, ethnic, political, or other divides, meaning their loss has civic implications and may contribute to the rise of public conflict and increased political polarization. “People say they now can’t or refuse to engage with friends or family members who think differently,” Finlay adds, “an intolerance they’ve never experienced before.”

Seismic changes in American work culture since 2020 are also threatening our weak ties.

As of May 2024, some 40 percent of Americans work from home at least one day a week and 26 percent work fully remote—a fivefold increase from pre-pandemic rates, according to Stanford University economist Nick Bloom. Data shows that change has been “overwhelmingly positive,” Bloom says, but it has also represented a cultural transformation that has companies struggling to catch up.

For many people, “technology doesn’t replace in-person time; it can’t replace all the physiological responses when we’re in person and all the random conversations that happen,” says Jim Harter, chief scientist for the workplace at the management consulting company Gallup. ” He stresses that remote work doesn’t have to lead to isolation or loneliness. But if how we work —from frequency of meetings to management style—doesn’t change accordingly, then “physical distance can become mental distance.”

Instead of “back to normal”

Widespread messages encouraging us to act as if everything is “back to normal” may in themselves be symptoms of trauma, Silverman says, since many people feel more comfortable speaking about difficult experiences once they’re resolved and “in the past tense.”

That dynamic may also contribute to the emotional, and often political, backlash against people continuing to wear masks—with the localities from North Carolina to New York City considering outlawing masks entirely. But it has heavy consequences amid waves of infections, continuing deaths, and risk of long COVID.

Finlay has found increased risk of depression and anxiety in those in her cohort still practicing COVID-19 caution. In their surveys, they say they feel abandoned and isolated watching the rest of the world appear to forget what for them is painfully present. And with public health guidelines lapsed and mask stigma increasing, “a lot of people are forced into even further isolation,” says Miles Griffis, cofounder of The Sick Times, which focuses on long COVID science and policy—a feeling akin to being “locked out of society.”

For both the coronavirus-cautious community and those returning to the habits of 2019, Fox feels that widespread acknowledgment of the struggles of the last four years, including from authority figures, is an essential first step toward healing. More possible steps: Finlay suggests reinvigorating weak ties through community programming; Altman points to rituals that make space for remembering the things that made this period so difficult.

Otherwise, people will continue to blame themselves for their continued distress. “I hear a lot of people saying, ‘I should be over this already; why aren’t I doing better?’” Fox says. “The truth is, this was so traumatic—how can we expect people to be over it? There’s a lot to work through.”

News

These manipulated photos are the original political deepfakes

Long before artificial intelligence, photographers altered images to burnish the reputations of politicians—from Lincoln to Stalin. The rise of artificial intelligence or AI has made photo manipulation easier and more accessible than ever. And under the right circumstances, these images…

These ancient cities sunk to the ocean floor. Here’s how they were rediscovered.

Lost cities sunken beneath the waves are not just myths. Many coastal communities were swallowed up by the sea in the ancient world—their streets, homes, and temples all submerged under relentless tides. For millennia legends swirled about these places, but…

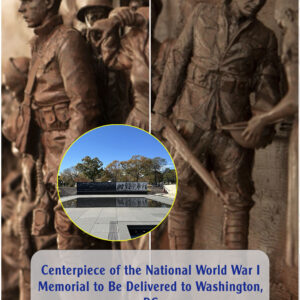

Centerpiece of the National World War I Memorial to Be Delivered to Washington, DC

Photo Credit: DANIEL SLIM / AFP / Getty Images Almost a decade in the making, the centerpiece of the National World War I Memorial is finally slated to arrive in Washington, DC. The 58-foot-long, 10-foot-tall bronze sculpture, called “A Soldier’s…

Offset Finally Speaks Out On Why He Chose Jade Over Cardi B Despite Having Two Children With Cardi B

Offset Opens Up About Choosing Jade Over Cardi B: A Closer Look Into Celebrity Relationships. In the whirlwind world of celebrity relationships, where headlines are often dominated by twists and turns, one particular love triangle has captured the attention of…

Cardi B Gets Into A Dispute With Milagro Gramz Following A Mishap At The Bet Experience Show.

Cardi B headlined the BET Experience Concert Series in Los Angeles, marking its return this weekend, but encountered technical difficulties during the show. Known for her passionate performances, Cardi B expressed frustration towards the production crew for missing cues, prompting…

Offset Finally Speaks Out On Why He Chose Jade Over Cardi B Despite Having Two Children With Cardi B

Offset Opens Up About Choosing Jade Over Cardi B: A Closer Look Into Celebrity Relationships. In the whirlwind world of celebrity relationships, where headlines are often dominated by twists and turns, one particular love triangle has captured the attention of…

End of content

No more pages to load