If there’s one thing aircraft carriers were known for during the Second World War, it was their role in changing the face of aerial combat. Whereas aircraft were previously limited to flying close to land, the massive vessels served as floating runways, allowing them to takeoff and land virtually anywhere in the world. While the majority of aircraft carriers sailed the world’s oceans during the conflict, two were stationed in the Great Lakes: the USS Wolverine (IX-64) and Sable (IX-81).

Turning luxury vessels into aircraft carriers

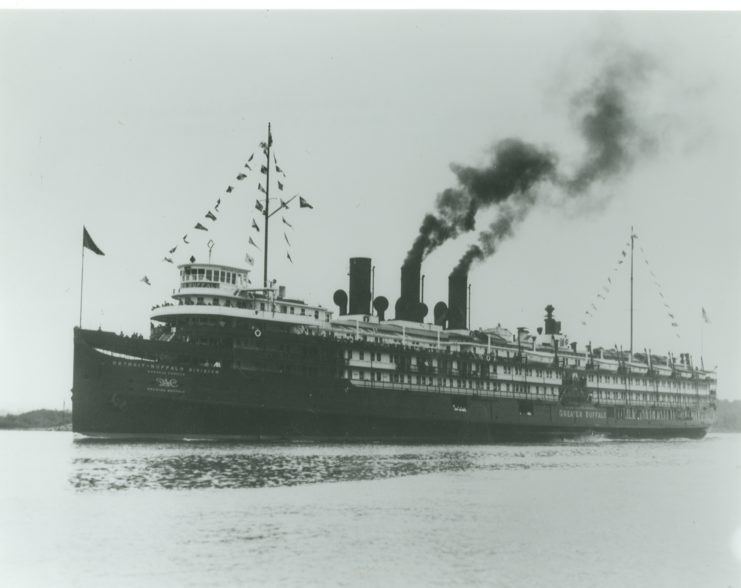

Greater Buffalo, 1942. (Photo Credit: Unknown Author / U.S. Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

While military officials initially shrugged off the idea, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor quickly changed everyone’s minds. The US Navy had a limited amount of aircraft carriers at its disposal, and all were needed on the front, so Adm. Ernest J. King ordered that Whitehead’s proposal be fast-tracked.

USS Wolverine (IX-64)

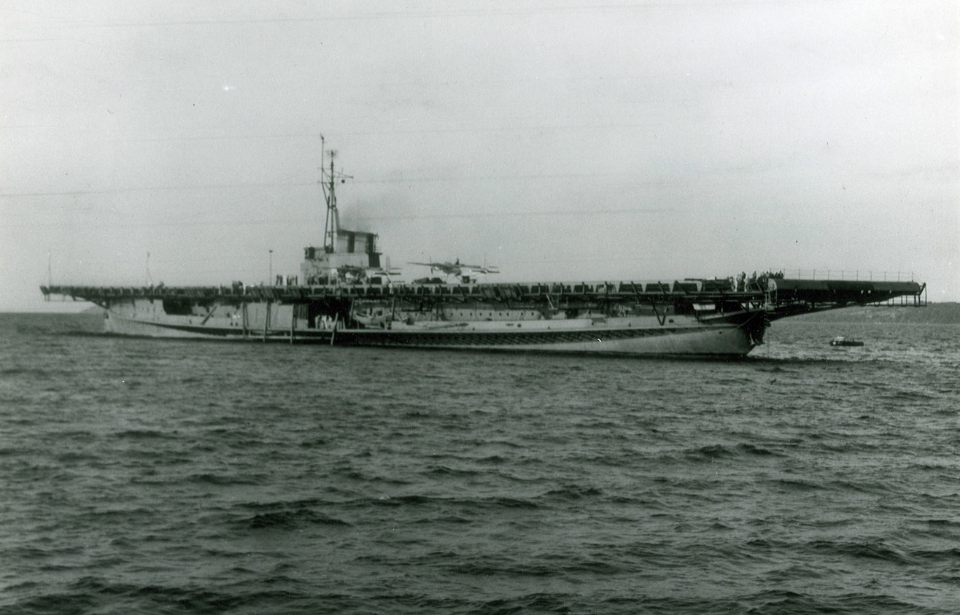

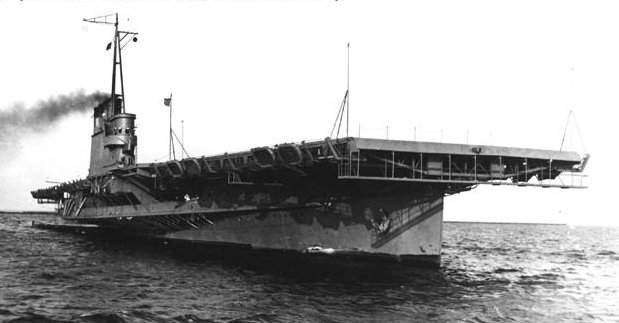

USS Wolverine (IX-64), August 1943. (Photo Credit: U.S. Navy / NavSource / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

Launched in November 1912 as the Seeandbee, the USS Wolverine was a luxury side-wheel paddle steamer that operated in the Great Lakes region. Capable of carrying up to 6,000 passengers and 1,500 tons of cargo, her typical route saw her travel between Cleveland, Ohio and Buffalo, New York.

In 1942, Seeandbee was acquired by the US Navy, with the intention of transforming her into an aircraft carrier. She was of particular interest to the service because her side-wheel paddles offered improved stability and maneuverability. To turn the steamer into an aircraft carrier, a 550-foot-long wooden flight deck, superstructure and arresting cables were installed.

Subsequently renamed Wolverine, the vessel, on the outside, looked like a miniature aircraft carrier. However, she was missing a number of key features that would have made her comparable to her larger, ocean-worthy counterparts. She wasn’t equipped with armaments, nor coated in armor, and was missing elevators and a hangar deck. As well, her flight deck was lower to the water.

USS Sable (IX-81)

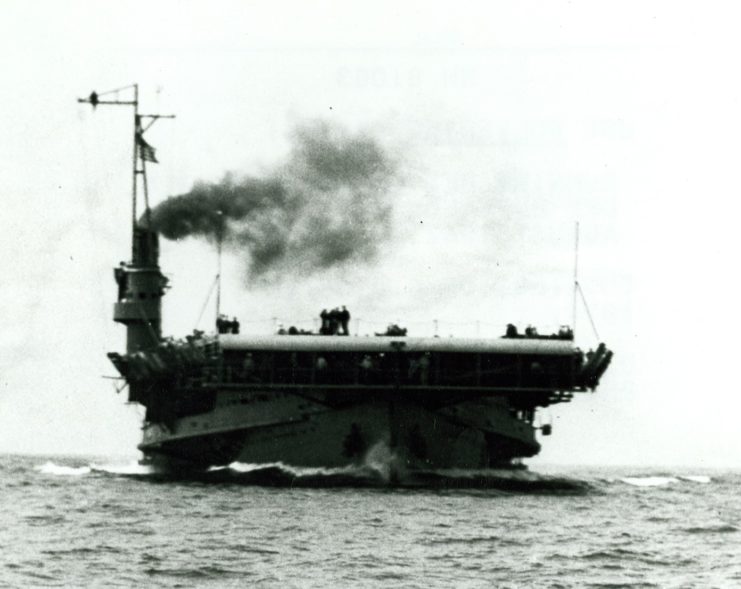

USS Sable (IX-81), 1944-45. (Photo Credit: U.S. Navy National Naval Aviation Museum / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

Launched in October 1924 as the Greater Buffalo, the USS Sable began life as a side-wheel excursion steamboat. Everything about her oozed luxury, with her Renaissance design affording her the nickname, “Majestic of the Great Lakes.” While operating in the Great Lakes in this capacity, she could hold over 1,500 passengers, 103 vehicles and around 1,000 tons of cargo.

Upon being acquired by the US Navy, Greater Buffalo had her cabins and superstructure removed. Steel supports were added, and, unlike Wolverine, she received a steel flight deck. While the vessel was initially meant to have a wooden one installed, the decision was ultimately made to go with metal, so the military could test non-skid coatings. Just like her sister ship, she was renamed – Sable – and wasn’t equipped with armaments, armor, elevators or a hangar deck.

An interesting fact about Sable during this time is that a large number of her crew members were survivors of the USS Lexington (CV-2), which had been lost during the Battle of the Coral Sea.

Training pilots in the Great Lakes

General Motors FM-2 Wildcat crashed into the flight deck of the USS Sable (IX-64), May 1945. (Photo Credit: U.S. Navy / Naval History & Heritage Command / U.S. Navy National Naval Aviation Museum / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

By 1943, both the USS Wolverine and Sable – nicknamed the “Corn Belt Fleet” – were stationed out of Navy Pier, in Chicago. They were assigned to the 9th Naval District Carrier Qualification Training Unit (CQTU), and operated throughout Lake Michigan.

Trainees were taught how to takeoff and land on aircraft carriers, with the idea being that, if they could successfully accomplish their tasks on the shorter flight decks, then the larger ones wouldn’t be an issue. While conducting their training, the pilots were made to keep their cockpits open, in the event of a crash, and to “graduate” they had to carry out 10 (later eight) takeoffs and landings.

Training occurred seven days a week. However, it was often curtailed due to a lack of wind over the decks of the aircraft carriers. In order for aircraft to effectively take off, they need a certain amount of wind, and the lack of it over Lake Michigan meant that heavy aircraft like the Grumman F6F Hellcat, Vought F4U Corsair, Douglas SBD Dauntless and Grumman TBM Avenger were unable to operate from them.

Over the course of the Second World War, Wolverine and Sable trained 17,820 pilots, including future US President George H.W. Bush, and were the sites of 116,000 landings. Fewer than 300 aircraft were lost. On top of training aviators, Sable was also used to test the TDR-1, a wooden remote-controlled drone.

Decommissioning of the USS Wolverine (IX-64) and Sable (IX-81)

USS Wolverine (IX-64), August 1942. (Photo Credit: U.S. Navy National Naval Aviation Museum / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

Following the end of World War II, both the USS Wolverine and Sable were decommissioned and struck from the Naval Vessel Register. Wolverine was put up for sale to the public, for either flag operations or scrapping, and wound up being sold for scrap in December 1947.

More from us: After 80 Years, the Fate Of the USS Cythera (PY-26) and Her Crew Still Remains a Mystery

The Great Lakes Historical Society tried to have Sable turned into a museum, but was unsuccessful. The vessel was eventually sold to the US Maritime Commission, cut down and scrapped.